The power of natural light 🌞—Windows: a battle between cameras and brains.

Sunlight is fundamental for humans when it comes to sight and photography. Too much of the sun’s light will burn your eyes retina or your cameras sensor. Not enough and you may find yourself stumbling in the dark or shooting into obscurity if your camera’s settings are not properly tuned. In this article, I will discuss the challenges photographers face when there is too much or not enough light while shooting interiors and how our minds perceive this reality.

To give you an example, our eyes have the ability to perceive light at a rate of 1– 1,000 ISO in comparison to the newest cameras that go from 50–102,400 expandable up to 204,800. ISO stands for the International Organization for Standardization. In photography, it refers to the sensitivity of a camera’s sensor to light.

Mirrored canon DSLR on the left and an image of my eye / iris on the right. ©️Matthew Bolt Photography 2025

When it comes to seeing reality and light, digital cameras cannot compete with the complexity of of the eye & brain’s biological connection and ability to process information — for now.

For example, our eyes contain 30 stops while the newest modern cameras contain 14 stops. A “stop” in photography is a unit of measurement for light. It’s a way to talk about the amount of light in a scene or the change in exposure, regardless of whether you’re adjusting the aperture, shutter speed, or ISO.

*Of note is that a stop is not the same as aperture on a camera. The concept of a “stop” is similar to understanding the human eye’s ability to see in different lighting conditions, particularly in terms of dynamic range.

For instance, our eyes can move 10–14 stops in an instance. Let’s say you move your glance inside your living room to look outside the window, your eye has just moved up in “stops” to what a camera perceives as “aperture”. When your eyes perform this action, within a millisecond your brain naturally shifts the focus and adjusts aperture or “stops” without even realizing it.

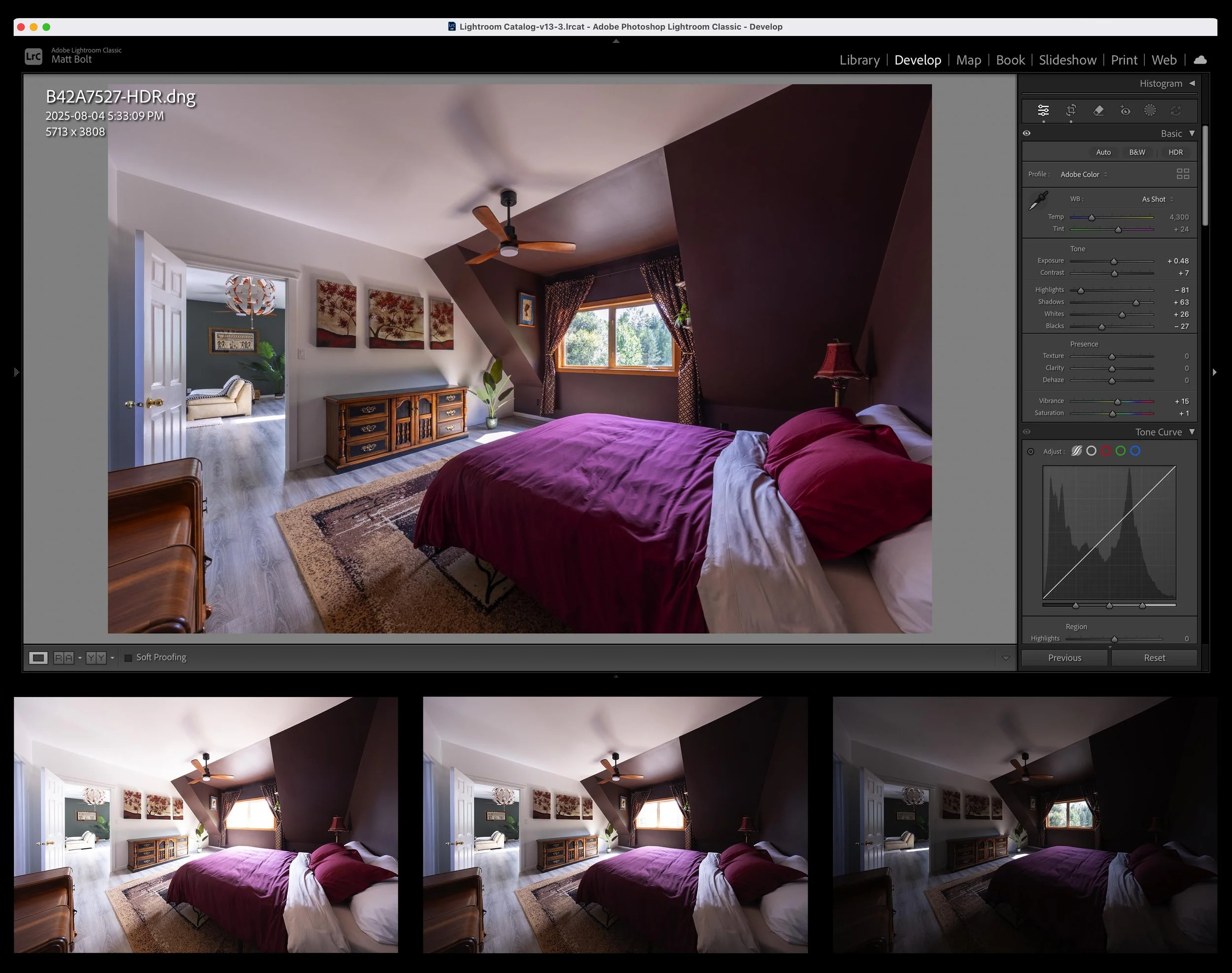

Modern day cameras such as the Canon R6 Mark II can perform this task of seeing both inside the living room and outside the window rather quickly using a technique known as HDR — High Dynamic Range. The camera takes 3 images (from light to dark) and merges them into one image. This operation takes the camera a mere .075 seconds. However, the results are lack lustre as images are often “flat” and lack contrast or a good focal point.

A screenshot of an HDR blend in Lightroom. The screenshot is the result of blending the bottom 3 images. The resulting blended image is very “flat”. Below is a quote from Kenrockwell on HDR photography

“HDR (High Dynamic Range): Our eyes do this with region-adaptable ISO. Sadly there is no HDR scheme yet today which successfully mimics our own visual system’s processing, which is why all the automated HDR images I’ve seen so far suck.”

Many clients (especially in real estate photography) prefer HDR photography because they feel like they can see “everything”. Usually this means they want to see the view the window offers. I can’t argue with wanting to see out of the windows and the client is always right. Throught my career as a professional photographer, I have done manual blending of images for windows (aka “window pulls”) that can be time consuming, but have greater focus during editing that make the scene appear more natural or artistic similar to the way the human brain perceives light.

While very useful, my main qualm with HDR photography is that our brains need a focal point or more contrasting elements to quickly process the image. After-all, this is how our eyes perceive light in reality, and flat images leave our eyes having to spend more time perceiving and understanding the image due to its lack of contrast and brightness.

Because I shoot primarily architecture, I pay close attention to light. When is the right time to shoot a home? The answer is when the client is ready! No, but seriously, we can’t control the weather and clouds can sometimes help photographers by creating a natural light filter that can make doing window pulls and controlling light and contrast easier. Also, a rainy day can make your images feel cozy too.

For interior photography, the best time to shoot is when the sun is overhead around noon — when the most amount of light is being let into the rooms of the home vertically. Shooting in the morning or afternoon is fine, but be careful of the orientation of the home and the windows positioning in relation to the way the sun travels. Going up against the sun (or lack there of) is challenging without the proper techniques or gear.

Windows are a big challenge for professional interior photographers. Successful photographers in the field will eventually develop a technique or style to deal with windows and intense light that is aesthetically attractive to clients and recognizable to their concurrence.

Image of of a college dormitory at Selkirk College Campus in Nelson, British Columbia for Cover Architects. Here I balanced the brightness of the windows by using luminosity blending masks. ©️Matthew Bolt Photography

When the going gets tough, good photographers use flash. A difficult challenge for interiors can be a big window allowing too much light in. If I am capturing an image, while shooting five stops of an interior scene on a tripod and notice that the windows are still not properly exposed and elements in the foreground are too contrasted and dark I will use strobes to address these issues.

While I try my hardest to stick to using natural light, artificial light can solve typical problems for these scenarios. This is commonly referred to as “flambient” photography. Flambient photography is when multiple exposures are combined with flash exposures. This editing process can be more time consuming but can also give the photographer more control over their images and produce more technical and professional results.

Image on the left — Aperture F9, Shutter Speed 1/10, ISO 400 image on the right — Aperture F9 Shutter, .8 seconds, ISO 400. Notice the heat haze occurring around the window. A flash or extra lighting would fix this.

The other challenge is when there is little or no light source for an interior shot. Cameras are better at seeing in the dark — they can have longer shutter speeds, higher ISO and be stabilized by a tripod for a crisp bright image. Because bathroom in the above image is painted dark purple and only has one window it is rather dimly lit. In the lighter image on the right hand side (I was shooting in aperture priority mode), the shutter stayed open a long time — almost a full second. Because I did not adjust the ISO accordingly (I could have bumped it up to 2000 ISO) a haze is created around the window. The mystery behind this haze is fascinating.

Our eyes contain rods and cones. Rods are in charge of low light vision and cannot see color and instead see shades of grey. The ISO in your camera is most comparable to the function of rods in our eyes. High ISO can yield noise or “digital junk”. This can happen in conjunction with longer shutter speeds. When you increase the ISO on your camera, you are asking it to become more sensitive to light and when you decrease the shutter speed you are asking it to stack photons of light on top of one another. What you witnessing in the swirling haze scene on the right hand image in the above photo happened because the camera’s sensor is capturing heat traveling through window combined with a long shutter speed.

In conclusion, I want to explain that cameras excel in one area versus our eyes, the absence of light — darkness (with some drawbacks). Our eyes will instantly adapt to light, wake us up when the sun rises and allow us to go throughout our day. In the absence of light, our eyes will take 10 minutes to adapt to dark environments and the rods continue to to adapt for 30–45 minutes. Cameras, on the other hand can be controlled to handle dimly light scenes within a few turns of dial — just be weary of dark rooms with small windows, this usually calls for the use of extra lighting. This goes the same for large bright windows.

For me, the best shot is one where I don’t have to constantly balance the image with multiple exposures. Some days the light will be perfect and some of my favorite images are not multiple exposures and required little to no editing — only knowledge of how to operate my camera.

Matthew Bolt is a professional photographer and an undisciplined creative with 16+ years of experience shooting architecture. If you have a moment please take a look at my websites:

www.matthewboltphotography.com

www.matthewbolt.com — UX

@matthewbolt_photography — instagram